From VFX Tools to Enterprise SaaS: Three Lessons in Finding Product-Market Fit

Ben Houston • 10 Minutes Read • July 26, 2025

Tags: entrepreneurship, coding, talks

This post is based on a talk I gave at TIE Ottawa on July 26, 2025.

Over the past twenty years, I've built software that's powered the visual effects in hundreds of Hollywood blockbusters—from Avatar to Harry Potter to Game of Thrones—and later helped Fortune 500 companies like Louis Vuitton, Starbucks, and Steelcase sell billions of dollars worth of products online. But here's the thing: none of this went according to plan.

The journey from accidentally creating industry-standard VFX tools to raising $65 million for an enterprise SaaS platform taught me three crucial lessons that every entrepreneur should understand. Today I want to share that story and those lessons, because they might save you from some expensive mistakes I made along the way.

The Accidental Beginning

My journey into entrepreneurship started with what might have been the most naive career move in tech history. In 2002, fresh out of university, I got an email from an old friend who'd joined Frantic Films, a visual effects studio in Winnipeg. "We need someone who knows computer graphics and coding," he said. I was so excited about working in Hollywood VFX that I didn't even wait for a contract. I bought a one-way ticket, stayed in a $20-a-night hostel, and just showed up to work on Monday morning.

They were genuinely surprised to see me standing there. I didn't have a signed contract, just a verbal "yeah, you got the job." But they gave me a computer, handed me Jos Stam's 1999 Stable Fluids paper, and said, "Here, write a fluid solver." Looking back, this was either incredibly naive or incredibly bold. Probably both.

I had a working 2D fluid implementation in three days. They were impressed enough to move me from the hostel to a hotel and actually negotiate my salary. Within five months, I had a 3D fluid solver that we showcased at SIGGRAPH 2003. This technology ended up being used on films like Scooby Doo 2 and The Core.

But the real breakthrough came from solving a personal productivity problem.

The First Pivot: From Personal Tool to Industry Standard

Fluid simulations took days to complete, which meant I couldn't use my computer for anything else while they ran. To solve this, I built a simple distributed scheduler I called "Cloud" that let me run simulations on idle machines throughout the office, freeing up my workstation.

Meanwhile, the studio was facing a completely different but much more expensive problem. They were using industry-standard software called Backburner to manage their 60-machine render farm for "The Core," but it was so unreliable they literally paid someone to work night shifts just to restart the server when it crashed. Without this human watchdog, they'd come in each morning to find failed renders and missed deadlines.

During a casual conversation about this insanity, we realized my little fluid scheduler could probably solve their much more expensive business problem. The key insight was to avoid the complexity that made other systems fail. Instead of building another complex central server, we used the Windows file system itself as our database. File renames handled locking, timestamps managed health checks. It wasn't fancy, but it was robust.

We deployed this system—now called Deadline—within a few weeks. No more overnight babysitting required.

Our first external client was Blizzard Entertainment, who needed reliable render management for World of Warcraft cinematics. After we got it working on their 120-machine farm, they gave us this endorsement: "Deadline made our network rendering problems a thing of the past." We even got a credit in the original World of Warcraft release.

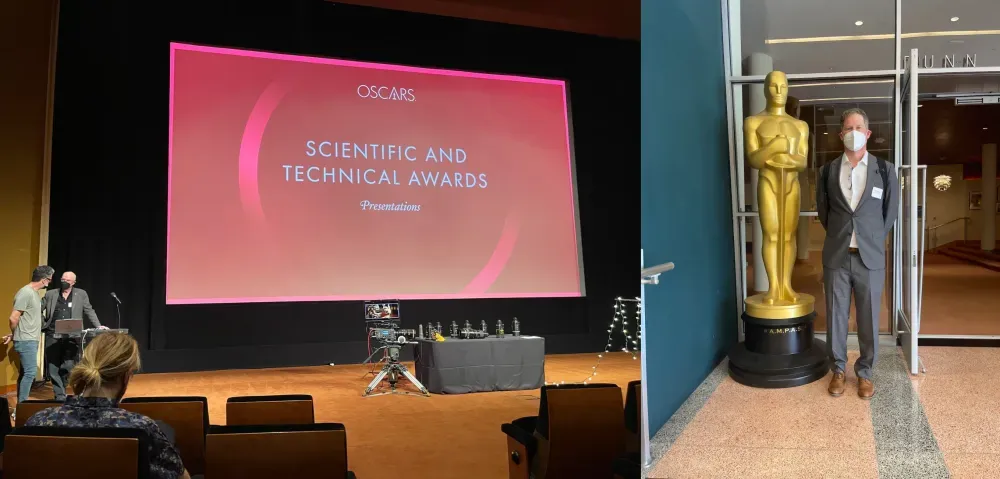

Deadline went on to be used on hundreds of major productions: Harry Potter, Game of Thrones, Star Trek, Star Wars, Transformers—virtually every VFX-heavy film of the past decade. It was considered twice for Academy Technical Achievement Awards and was eventually acquired by Amazon. All because I needed a better way to run my fluid simulations.

Building Ownership

By 2005, I had proven I could build successful products, market them, and personally sell to major clients. But there was one crucial thing missing: ownership. While I was helping build successful businesses, I wasn't building toward my own success. That realization changed everything.

I left Frantic Films and founded my own company, Exocortex. I started with consulting but wanted to build products, not just sell my time. So I negotiated to keep the IP from consulting projects and turned that into VFX plugins for Maya, 3ds Max, and Softimage. We got clients like Industrial Light & Magic, Ubisoft, and Method Studios, contributing to films like The Avengers and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter.

But by 2012, I was ready for a bigger bet.

The $1 Million Learning Experience

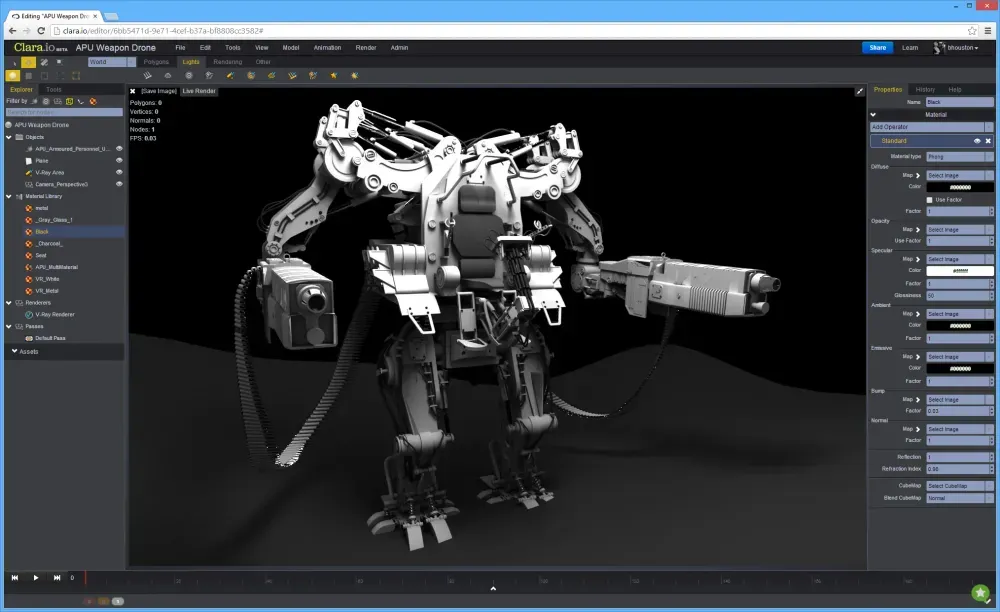

Watching the web transform how we use software—Microsoft Office losing ground to Google Docs not because Docs had more features, but because it was more convenient—I thought: what if we could do the same thing for 3D editing? Create a platform that worked on any device, saved to the cloud, enabled real-time collaboration, and used cloud rendering so you didn't need expensive hardware.

We launched Clara.io at SIGGRAPH 2013 to tremendous excitement. Presenting a fully functional 3D editor running in a web browser to an auditorium of 200 people, we got a standing ovation. Within 18 months, we had over 100,000 users, significant media coverage, and angel investors including Marc Petit, the former SVP of Autodesk.

But we had a fundamental problem: students and hobbyists loved Clara.io, but professionals couldn't use it for serious work. Browser memory limitations meant we couldn't handle complex projects. Professional 3D artists, deeply invested in their existing tools, needed every possible feature. I had fallen into the classic innovator's dilemma—our new technology served the low-end market well, but couldn't meet the needs of high-value customers. And students don't pay enterprise software prices.

I was genuinely confused about what to do next. Here I was with 100,000 users, media coverage, and prestigious investors, but I couldn't monetize it effectively. I felt like I was watching a slow-motion train wreck.

The Second Pivot: When Constraints Become Advantages

Then we got an unexpected call. Steelcase, one of the largest office furniture manufacturers in the US, asked if we could use our technology to help customers visualize highly configurable office chairs on the web. This was not my vision at all. I was building the future of 3D collaboration, not a product configurator for office furniture.

But we were running out of money, so I said yes.

This pivot was brilliant because it completely flipped our constraint. With Clara.io, being web-based was a limitation—professionals needed desktop-level performance. But for product visualization, being web-based was essential. Steelcase customers needed to see configurable furniture in their browsers, not download desktop software. We went from fighting against our platform's limitations to leveraging its core strength.

A few months later, we had a six-figure annual contract with Steelcase. Success bred success: Steelcase recommended us to Crate & Barrel, Herman Miller heard about our work and brought us into a competitive RFP. Suddenly we had validation across multiple furniture brands and a clear path to building Threekit.

Scaling Beyond Individual Capability

But I had a problem. We had great technology and clear product-market fit, but I lacked expertise in systematic sales processes, raising significant capital, and scaling operations quickly. I'd seen this before—in fast-moving markets, it's not the best technology that wins, it's the best overall package.

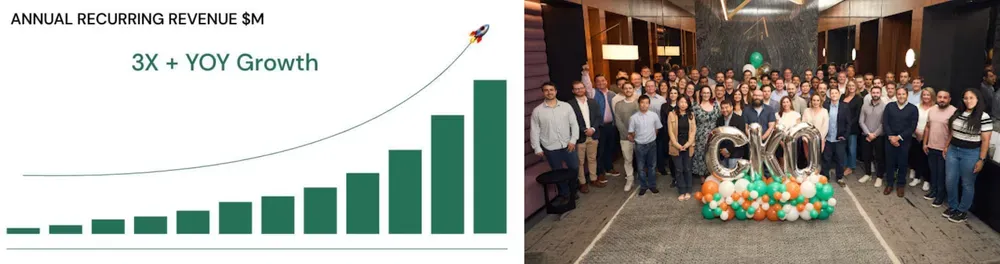

That's when we met a serial entrepreneur who had already solved this exact problem. He had built and sold two companies in the product configuration space—one to Oracle for $300 million, another to Salesforce for $300 million. In 2018, we did a deal where he took majority control, bringing in proven operators as CEO, COO, and head of sales, while I focused on technology.

The results speak for themselves. We raised $65 million, grew from 20 to over 100 employees in three years, and achieved 3x revenue growth. Today, Threekit serves luxury brands like Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior, major retailers like Starbucks and Crate & Barrel, and manufacturers like Steelcase and Milwaukee Tools.

Three Hard-Won Lessons

Looking back at this journey, three crucial lessons emerge that every entrepreneur should understand:

Lesson 1: Pivot Toward Better Product-Market Fit

Your initial vision isn't always where you find success. This happened to me twice—my fluid simulation scheduler became Deadline, and my 3D collaboration platform became Threekit. Both times, I was solving one problem and discovered a much better business opportunity.

The key is being prepared to listen to what the market is telling you, even when it's not what you want to hear. With Clara.io, I spent over $1 million and two years building something that attracted 100,000 users but couldn't generate sustainable revenue. One phone call from Steelcase changed everything. Same core technology, different problem, completely different business model.

Sometimes what you think are your biggest constraints actually become your greatest advantages in the right market.

Lesson 2: Focus on Enterprise Customers

Early on with Threekit, we sold to anyone who would buy. But I learned that small businesses and startups are price-sensitive, have high churn rates, and offer limited expansion potential. Enterprise customers have higher budgets, accept longer-term commitments, and offer massive expansion opportunities.

Once we focused exclusively on large enterprises (200+ employees), a lot of the chaos in our business disappeared. We no longer fought to get bills paid, our churn dropped dramatically, and our customer service team could focus on a manageable number of high-value relationships.

With enterprises, that initial $100,000 project is just the beginning. Once you've proven yourself, expansion becomes much easier because finance and legal already know you, you've built credibility through successful delivery, and you understand their internal politics. Customer Success Managers who focus on growing these relationships often drive the majority of revenue growth.

Lesson 3: Enterprise Customers Buy the Complete Package

Your product is only part of what enterprise customers are buying. They're actually purchasing three things: the product itself, the integration of that product into their existing workflows and infrastructure, and the long-term professional relationship with your team.

Complex software is useless unless it's properly integrated, and complex projects inevitably have hiccups that require strong relationships to resolve. This is why experienced enterprise customers often prefer working with boring but professional vendors over cutting-edge but unproven ones. They know there will be fires to put out and miscommunications to resolve.

They're not just buying your technology—they're buying your ability to be a reliable partner through a complex, multi-year relationship.

The Bigger Picture

Looking back, I'm incredibly proud that software I created as my first job out of university has helped create some of the most visually spectacular films of the past two decades, and now helps major brands sell billions of dollars worth of products online. It's proof that with the right problem, the right solution, and the willingness to pivot when you find better opportunities, you can build something that changes entire industries.

But the most important lesson is this: you don't need to start a traditional startup to have massive impact. Some of the best opportunities come from solving problems right where you are. My biggest successes—Deadline and Threekit—both started as solutions to immediate problems I was facing, not grand entrepreneurial visions.

The key is staying alert to those moments when a small problem reveals a much larger opportunity, and being brave enough to pursue it even when it takes you somewhere completely unexpected.